<< No strings attached. You can always unsubscribe!

#03 - december 2025

GUT RENO OR SMART INTERVENTIONS

Many architects say that once you start fixing parts of an old building, you might as well redo the whole thing. Their point is that if you change the wiring in one spot, you may have to update all of it. If you level a floor, the stairs might no longer line up. If you change one room, suddenly all the floors might need replacing. Sometimes this really does happen.

But you don’t always have to go all-in. There’s another option: make only small, smart changes. You can leave some areas exactly as they are, but add a new doorway, build a new staircase, or repair just the spots that need it. If you do this carefully, the mix of old and new can actually look cool—almost like a modern design idea on purpose. And when these small changes are planned well and make the space feel great, you end up with something we can call “smartism”: fixing only what matters, and making the building better without tearing everything apart.

REM KOOLHAAS

If "smartism" is about fixing only the important stuff and leaving the rest alone, then the world-famous architect Rem Koolhaas is basically the master of the style. Most architects think that if you renovate an old building, you have to scrub it clean until it looks brand new. Koolhaas thinks differently. He treats buildings like a remix—he keeps the gritty, old beats and layers a new, modern melody on top.

He realized you don’t need to hide a building’s age to make it cool. In fact, the cracks and stains give it character.

His work on the Prada Epicenter in serves as a definitive case study for this approach. Located in a landmarked district of SoHo, the site was a former industrial space with a heavy, historic atmosphere. A more conventional renovation might have sought to level the floors or conceal the weathered walls to create a standard, polished luxury environment. Koolhaas, however, embraced the building's imperfections. He left the original masonry, peeling textures, and structural grid largely exposed, acknowledging the space's past life.

Then, he did the "smart" part. He built a massive, curving wooden slope right in the middle of the store. This element does not try to blend in; it creates a distinct separation between the untouched enclosure and the new retail function.

This is why "smartism" works. By ignoring the small repairs and focusing on one awesome feature, Koolhaas created a space that feels historically grounded and contemporary. He proved that you don’t have to tear everything apart to build something great; you just have to be smart about what you add.

INTERIOR RENOVATION

If your building is located in a Landmarked District but is not an individual landmark—which is the case for almost all landmarked homes—the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is hands-off regarding the interior.

You will still need to file for a Certificate of No Effect with the LPC to confirm that your work won't impact the building's exterior envelope. As long as your renovation doesn’t alter the façade, structural walls, or visible window profiles, this approval is typically administrative and fast.

This gives you immense creative freedom behind closed doors. You can radically modernize a floor plan or open up a parlor floor while strictly preserving the historic streetscape.

From an investment standpoint, updating the interiors of a historic home is often the smart move. Bringing mechanical systems, kitchens, and layouts up to modern luxury standards yields a substantial premium at resale, bridging the gap between old-world charm and contemporary comfort.

Executed properly, you get the best of both worlds: historic prestige on the outside, modern luxury on the insid

#02 - october 2025

CRITICAL CONTRAST

When updating or expanding a landmarked townhouse, should you aim for imitation or for a dialogue between eras? Steven Holl’s Pratt Institute Higgins Hall extension (2005) offers one answer. Instead of replicating the 19th-century brick buildings it connects, Holl inserted a distinctly modern glass-and-metal bridge with irregular windows. The contrast makes the historic facades more legible, but also asserts a bold contemporary presence.

This approach, often called critical contrast, is rooted in the Venice Charter’s idea that new work should be distinguishable from historic fabric. Supporters see it as honest and respectful of history; critics worry it can overwhelm or distract from the original character.

For townhouse owners, the choice is ultimately a philosophical one: should additions blend seamlessly into the past, or should they declare themselves as products of their own time? Holl’s work illustrates the impact — and the controversy — that comes with choosing the latter.

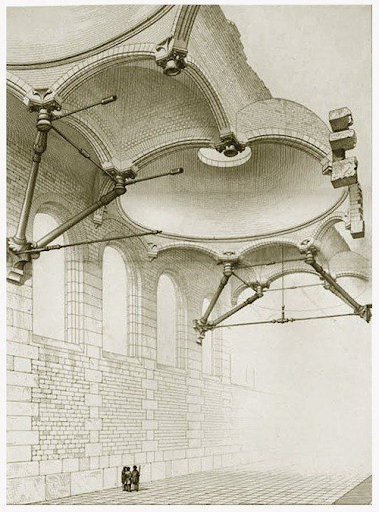

VIOLLET-LE-DUC

The debate about whether to design in harmony with the style of an existing building or to deliberately contrast with it is nearly as old as the oldest buildings in our city. In the 19th century, the French architect and theorist Eugène Viollet-le-Duc took a clear position on this question — one that remains provocative in preservation circles today.

Viollet-le-Duc believed that restoration and alteration should aim to realize the “spirit” of a building, even if that meant making changes the original builder never conceived. For him, fidelity to an idea was more important than fidelity to the exact materials or details. Stone could be replaced with iron, brick with glass, as long as the intervention respected the building’s structural logic and character. He was unafraid to use contemporary techniques and designs when he felt they completed or advanced the architectural intent.

Applied to the modern debate on landmarked properties, his stance sits somewhere between imitation and contrast. Like those advocating for critical contrast today, he would reject false historicism — the idea of disguising new work as old. Yet unlike some advocates of sharp juxtaposition, his goal was not necessarily to set old and new in opposition, but to integrate them in a way that continued the building’s narrative.

This might mean adding a rear extension in steel and glass if that approach supports the building’s function and spirit, or it might mean reconstructing missing ornament in a compatible but subtly updated form. The material and style could change; what mattered to Viollet-le-Duc was the coherence of purpose.

In this view, preservation is not just about freezing a building in time, but about allowing it to evolve — provided each change grows organically from the architectural story already being told.

SECONDARY FACADE

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) takes a very different approach to different parts of a building, and these distinctions tie directly into the long-running debate between critical contrast and the more interpretive philosophy of Viollet-le-Duc.

On a primary façade — the street-facing front that defines a building’s public character — LPC rules lean firmly toward historical fidelity. Repairs must generally be “in-kind,” matching original materials and details. Here, critical contrast is almost never permitted; the goal is to preserve the precise look and feel of the historic streetscape. Viollet-le-Duc’s idea that any material could be used, so long as the spirit of the building was maintained, finds little room here — the Commission’s focus is on material authenticity, not reinterpretation.

Secondary façades — side or rear elevations — are treated with more flexibility, especially when they are less visible from public streets. Here, small-scale contemporary interventions, additions, or modern materials may be approved, so long as they don’t overwhelm the historic form. This is where the spirit of Viollet-le-Duc can occasionally surface: a new glass rear addition, for example, could be read as both a contemporary contrast and a continuation of the building’s functional story.

In short, LPC policy keeps the public face of a landmark in its historic language, while offering more space for architectural “conversation” on its quieter sides.

august 2025 - issue #1

BEYOND THE 'FACADECTOMY'

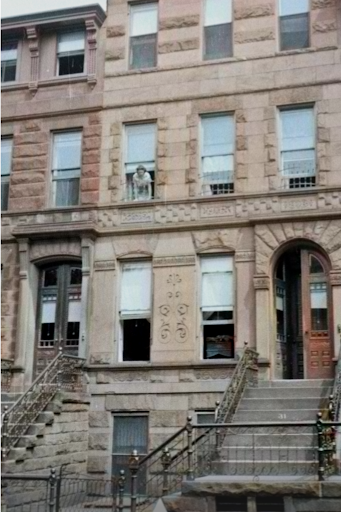

If you own a landmarked townhouse in Brooklyn, you know renovation isn't simple. It's a conversation between past and present — and how you choose to honor both.

Take the Domino Sugar Refinery in Williamsburg. Its historic brick façade was preserved, but behind it? A brand-new glass building. It's visually stunning, but critics call it a "facadectomy"— keeping the outer shell while erasing the building's original soul.

The other approach is slower, messier, and more rewarding: preserving not just how a building looks, but how it lives. That means working with original floors, moldings, even quirks — revealing the layers of history instead of covering them up.

As a homeowner, you have a choice. You can modernize without starting from scratch. Every patch of plaster and salvaged fixture tells a story — including your own.

Good renovations respect what came before while making space for what's next. After all, you're not just preserving a house; you're preserving a piece of history. You're continuing a legacy.

BARCELONA

When we talk about preserving historic buildings, especially in cities like New York, the conversation often gets framed in black and white: either you keep everything exactly as it was, or you gut the interior and slap a modern design behind a preserved facade. Both approaches have their place—but neither fully captures the creative potential of working with history.

A more nuanced way forward is emerging in places like Barcelona, where architects are showing how to renovate historic buildings with care, imagination, and respect. In many apartment renovations there, designers embrace the character of aging structures—think decorative tile floors, exposed brick, plaster walls, and carved wood doors — while inserting bold new spatial elements. These additions might include floating staircases, built-in mezzanines, or glass- walled rooms that lightly touch the original shell.

Rather than hiding or polishing over age, the old elements are left visible—cracks and all. The past becomes part of the experience, not just a decorative layer. These spaces feel deeply lived-in, yet completely contemporary. They're flexible, functional, and far from precious.

It's an approach that could serve us well in Brooklyn and beyond. Historic homes here have rich bones: high ceilings, detailed moldings, and quirks that tell a story. Instead of wiping the slate clean or freezing it in time, we can think of these buildings as layered canvases — where new design can coexist with the old.

This mindset invites creativity. It also fosters a deeper connection to place. You're not just preserving architecture; you're participating in its evolution.

Preservation doesn't have to be about locking a space in the past. It can be about uncovering, responding, and thoughtfully adding to what's already there. When done well, the result isn't just a beautiful space—it's a living history you can walk through.

DONUT HOLE

If you own a landmarked townhouse in NYC and are considering a rear extension, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) has some clear — and surprisingly reasonable — guidelines. They refer to the open space behind city blocks as the “donut hole.” If at least 25% of that donut hole already includes rear extensions, LPC will typically allow you to build a one-story extension as of right.

If fewer than 25% have extensions, LPC evaluates the context. If you can document a pattern of existing additions — even scattered one- or two-story ones — you may still have a strong case, especially with a design that’s sensitive to the building’s character.

Looking to go two stories? If neighboring buildings have similar extensions, your chances are even better.

From an investment standpoint, adding square footage is one of the smartest moves a townhouse owner can make in NYC. On average, added space can increase your property’s value by 30–60% more than the cost of construction — a rare return in this market.

Done thoughtfully, a rear extension enhances both lifestyle and long-term value.